Deconstructing the Stigma: On Black Mental Health

- 1 February 2021

- ByRobert Jenkins

- 2 min read

Big Cartel Art Works is our initiative to provide work, opportunity, and creative freedom to artists in this time of uncertainty. As the pandemic has intersected with overdue discussions on racism and inequality, we'll be commissioning some projects that stretch beyond our normal areas of expertise. Right now, it's time to learn and elevate stories that we all need to hear.

We're doing our work to understand - and undo - the harm caused by systemic racism and racist atrocities. Today, Antoinette Thomas and Robert Jenkins uncover the stigmas that surround the mental health of Black people.

“When you look at the historical experience of African Americans in the United States, you have to start with the experience of slavery and the vestiges in terms of the traumas associated with it.” - Dr. Michael A Lindsey

Growing up, discussing mental health was taboo within my family. As someone who dealt with both depression and anxiety as a teen, it wasn’t something that was talked about. The consensus of my parents was that we didn’t have time to worry about being mentally healthy, or even physically healthy.

We were too busy trying to survive “the white man's world.” We didn’t have the time to be sick.

This ideology makes sense when I look back on the context of my family's history, a people who were once enslaved. Back then on a plantation, expressing that you were sick, tired, or angry at your circumstances could mean a whipping or death. It was best to just do what was expected of you to survive. But holding all that pain in has had generational consequences for my family and many others in the Black community.

According to the National Alliance on Mental Illness, “Black adults in the U.S. are more likely than white adults to report persistent symptoms of emotional distress, such as sadness, hopelessness and feeling like everything is an effort.” However, only 1 and 3 Black adults in the US receive the help they need. This is due to several factors, all of them tied to America’s past - things like:

Disproportionate access to mental health resources

Mental Health misdiagnosis

Stigma around mental health

These are all a result of systematic racism that evolved from white supremacist ideas during slavery, perpetuating lies and stereotypes suggesting Black people are less-than-human.

The psychological, physical, sexual, financial, and emotional traumas of slavery still echo in the blood of America. It is like a ghost, a powerful poltergeist in the air of the nation. Prayers have been said and holy water has been thrown, but it has not yet to be fully exercised just yet. But I believe this is because the devastating effects of these traumas haven’t been widely acknowledged in all of its forms, even in the Black community.

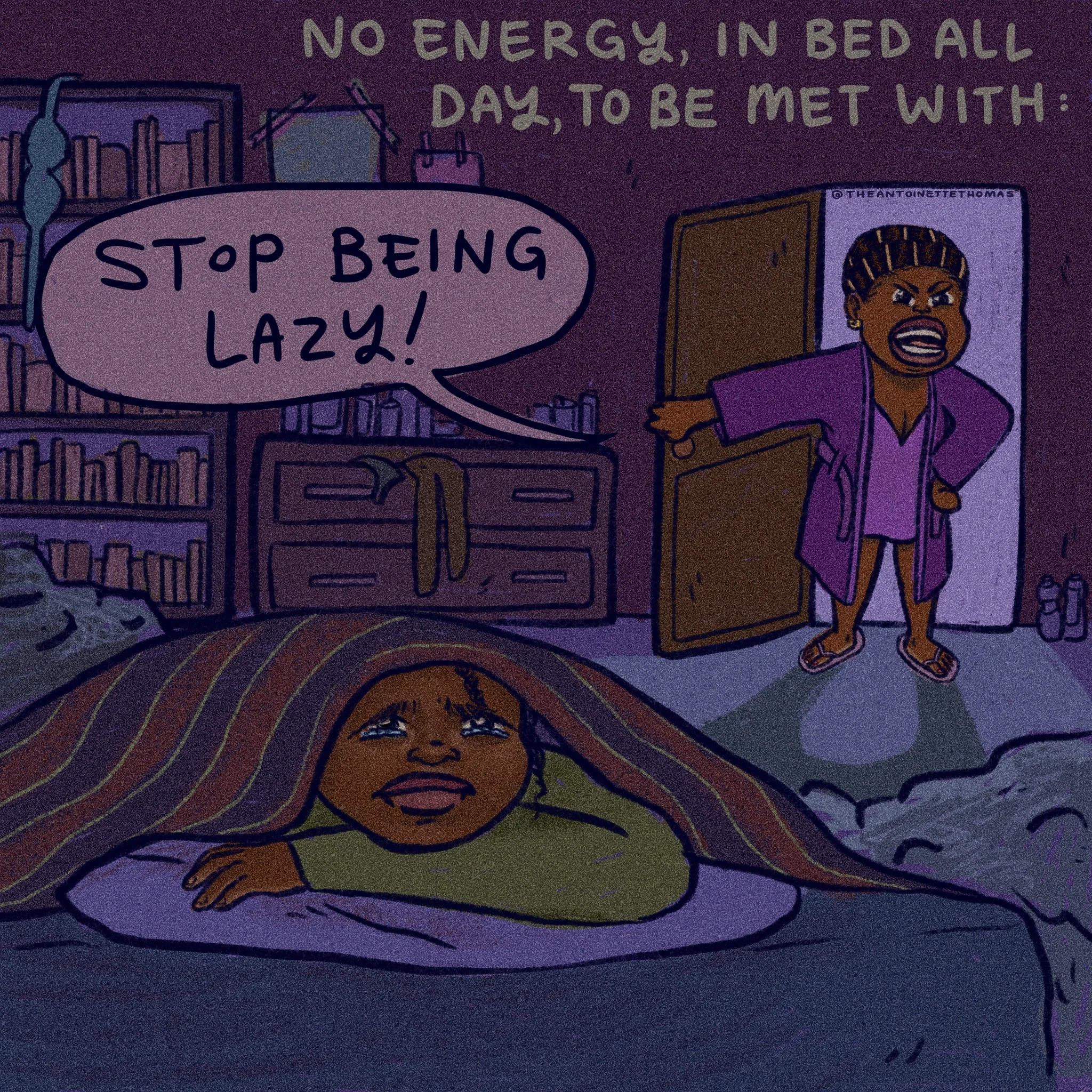

Being grown now and speaking to many of my Black peers about their experiences, I see I wasn’t alone. Many of my peers, when they showed signs of depression or anxiety, were labeled to be “weak,” “lazy,” or “extra,” even when their parents would show signs of mental and emotional distress as well. Many times when I would bring up therapy to my elder relatives, they would dismiss it. Some even commented that therapy was for white people.

Illustration by Antoinette Thomas

The reason for this mental health stigma among the Black community is once again tied to America’s past.

In fact, from the 1700s to the mid-1800s, enslaved Black people were thought to be immune to mental illness. The logic then was that mental illness could only affect the people who primarily dealt in commerce exchange, and because enslaved Blacks didn’t have any money, there was no way they could suffer from any mental illness. Conveniently, white men could and should be treated for mental illness, as they were the ones who had the money. This was called “The Immunity Hypothesis.”

There were some exceptions where enslaved Blacks were able to be treated, but this was only with permission from and under the supervision of their owners. Even when Blacks were able to receive mental health treatment as free people, it was weaponized against them. A census in the 1840s would report that “free blacks in northern cities experienced significantly higher rates of mental illness than enslaved blacks in the south.” This was of course to try to paint the picture that Black people were happier and healthier when enslaved, forgetting to mention the fact that there were restrictive laws in the South when it came to admitting enslaved Blacks to mental institutions, meaning there were less enslaved Blacks allowed to even be admitted.

There were also doctors like Samuel A. Cartwright who propagated the idea that enslaved Blacks desiring to be free from their slave owners suffered from a mental illness called “Drapetomania.” This “illness” would cause them to attempt to run off the plantation to freedom. Cartwright proposed that in order to prevent this illness from taking hold, that slave owners should whip “the devil” out of them. (It should be noted that white indentured servants would also run away, but them wanting to flee wasn’t viewed in the same way.)

Ideas like Cartwright’s also influence how Black people were treated within mental institutions. Black patients were segregated from the whites, often kept in low-grade conditions compared to their white counterparts. The Black people there were also neglected and abused, made to labor in the field, kitchen, or laundry room, while the white patients were allowed leisure activities such as being able to plant in a garden or sew.

When examining this history, it’s not a surprise to hear some of my elders remark that “therapy is for white people.” The idea was passed down that it was safer to just endure through their pain rather than seek help to heal it. Historically, the health system was built to serve and cater to the needs of white people, many times at the expense of our own.

In recent times, there have been signs that the stigma surrounding mental health in the Black community is starting to lift. Black voices like actress Taraji P. Henson have started a free online therapy service, specialized for the Black community. The Daily Show with Trevor Noah recently did a segment called “Black Mental Health - If You Don’t Know, Now You Know,” where he highlights many of the things I discussed here.

Black people are speaking out, taking action to raise awareness of this issue, and we should continue to do so. Only through acknowledgment of the pain of the past can we heal it.

1 February 2021

Words by:Robert Jenkins

Tags

- Share